Lasers became popular with movies like „Star Wars“ or „James Bond“. In reality, lasers are incredibly versatile applicable tools. Physicists of the University of Stuttgart succeeded with a technological breakthrough which will extend the choice of by semiconductor lasers accessible wavelengths. This in turn will facilitate new applications.

Today, depending on their power, beam quality and wavelength, lasers are used, e.g., for cutting and welding of a variety of materials or as a sensor that scans the data stored on DVDs or Blu-Ray Disks. Due to their compactness semiconductor lasers are particularly suited to be integrated in complex devices. However, semiconductor laser diodes have several drawbacks compared to other laser systems like gas lasers or solid-state lasers: The output power of such laser systems cannot be reached and the intensity distribution of the emitted beam strongly deviates from the optimum Gaussian beam which describes the best possible focusing capability. This focusing capability by the way is the crucial parameter to efficiently couple a laser beam into an optical fiber.

The invention of the solid-state-thin disk laser, also from scientists of the University of Stuttgart some years ago, fructifies also the area of semiconductor-based lasers. The disk laser concept improves the heat dissipation from the laser medium drastically preventing an early overheating or even its destruction. The operational limits of such systems are shifted by this to much higher powers.

By realizing semiconductor lasers as disk lasers these devices are in no way inferior in terms of beam quality compared to conventional systems like yttrium-aluminum-garnet-lasers or helium-neon-lasers. This for example is essential in the modern medical technology for minimum invasive surgeries with optical fibers.

How can semiconductor disk lasers further be improved in terms of output power without losing their other wonderful properties? Scientists from the “Institut für Halbleiteroptik und Funktionelle Grenzflächen” around Prof. Dr. Peter Michler and from the “Institut für Strahlwerkzeuge” around Prof. Dr. Thomas Graf and Dr. Uwe Brauch examined this issue. The key solution sounds simple and is consequent though challenging as it is in most cases when going into practice. Semiconductors themselves are poor thermal conductors. So one has just to omit all parts of the semiconductor structure not essentially necessary to build up a whole laser: the substrate on which the semiconductor layers are deposited has no function during laser operation and can be removed. External mirrors can replace the semiconductor mirror, integrated in all semiconductor disk lasers.

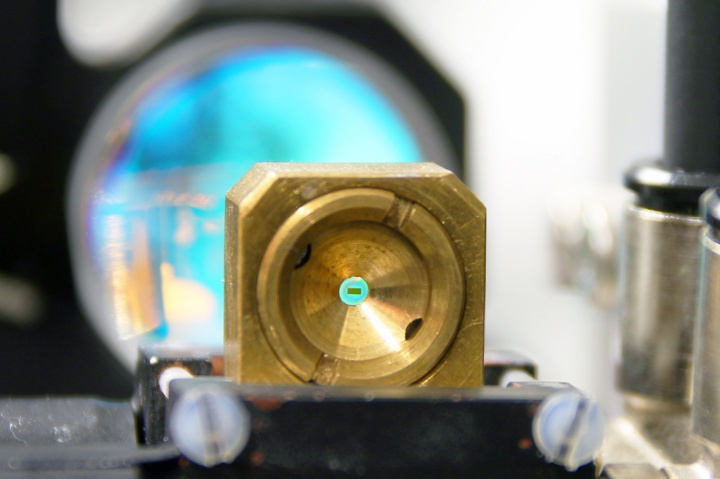

The only thing left of the semiconductor component is the several few hundreds of nanometers thick laser active region which gets sandwiched between two diamond disks. Diamond – transparent and the best thermal conductor available – is suitable in an outstanding way as an integrated heat spreader. The PhD-Students Hermann Kahle and Cherry May Mateo started with wet-chemical etching processes to isolate the laser active region from its substrate. The semiconductor membrane, in total thickness only one eightieth of the diameter of a regular human hair, can be stored and best handled when submerged in a liquid only. The exciting thing at the end was to transfer the membrane onto a diamond disk which is four millimeter in diameter and 0.5 millimeter in thickness. Likewise, it has to keep in one piece, centered to the diamond and totally flat. And, there was never a second chance. Once bonded to the diamond by capillary forces it was impossible to remove the membrane again without destroying it. Laboratory work like this requires calm hands, lots of skill and endurance. “We had to start again and again very often but in the end the efforts paid off.” The completed diamond-semiconductor-sandwich was then inserted into a laser resonator and characterized in the optics laboratory.

Hours of adjustment

After hours of adjustment work it flashed and the membrane laser was operating. A strong light beam in the red spectral range was emitted after a little more fine adjustment. And, it showed all characteristics we had hoped for: the tunability of the laser wavelength during operation, a perfectly shaped beam profile and especially a for semiconductor lasers high output power; and all this at an operating temperature of 10°C. Without the diamond sandwich the semiconductor membrane would rapidly overheat and stop to operate. Before this approach the whole semiconductor disk laser device sometimes had to be cooled down to minus 30°C.

An important intermediate target has been successfully accomplished; detailed work starts now. The data gained until now attest the scientists that they have developed an attractive novel laser system carrying further benefits. Omitting the integrated semiconductor mirror a performance hampering heat barrier disappeared. Furthermore, this extends the accessible emission wavelengths as material intrinsic absorption effects of the semiconductor mirror also disappear. The formerly integrated semiconductor mirror builds up the laser resonator together with an external mirror. This resonator is essential for laser operation. Now the integrated mirror is replaced by an additional external mirror to complete the laser resonator.

In future we will be able to realize further lasers with this technology which up to now have been impossible to realize as compact semiconductor based lasers operating in colors like yellow or orange. Even physicians can be looking forward to this. In the medium term new fiber coupled lasers for the photodynamic therapy could be available, operating at room temperature. Additionally, these lasers are tunable in emission wavelength and can be adjusted to the wavelength necessary for the used light sensitive drug due to the beneficial characteristics of semiconductors.

“We are asked occasionally if the light saber from Star Wars will be available soon.” Science-fiction fans need not to worry: “We’re working on that.”

Expert Contact:

Hermann Kahle und Michael Jetter, Universität Stuttgart, Institut für Halbleiteroptik und Funktionelle Grenzflächen, Tel.: +49 (0)711 685 -60499 oder -65105, hermann.kahle[at]ihfg.uni-stuttgart.de, michael.jetter[at]ihfg.uni-stuttgart.de

Originalpublikation: Hermann Kahle, Cherry May Mateo, et al: Semiconductor membrane external-cavity surface-emitting laser (MECSEL), Optica 3, 1506-1512 (2016).

https://www.osapublishing.org/optica/fulltext.cfm?uri=optica-3-12-1506&id=356211