More than 440 people were wronged

During the years under National Socialist rule in Germany from 1933 to 1945, many people who were researchers, students, or forced laborers were disenfranchised and persecuted at Technical University of Stuttgart.

During the memorial event, Rector Prof. Wolfram Ressel, on behalf of the University, asked the families of victims for forgiveness for the injustice. Before the event, all traceable personal stories were researched and documented for the first time. Project manager Dr. Norbert Becker explains the facts behind the documentary in a video.

Apology and appeal

Occasioned by the completion of the documentary, the University of Stuttgart held a memorial event during which Rector Prof. Wolfram Ressel extended a formal apology to the families of the victims. He also expressed appeal, pointing out that – contrary to sentiments conveyed in 1946 – science and teaching were never unpolitical, nor should they be.

On behalf of the University of Stuttgart, I ask all those affected and relatives of those persecuted for forgiveness for the injustices they and their relatives had to endure at the hands of the Technical University of Stuttgart...

Prof. Wolfram Ressel, Rector, Memorial event, February 6, 2017

Persecution and disenfranchisement

Three among many

Paul Peter Ewald was looking forward to a promising professional life in the sciences. He even made it to the position of rector. His career in Germany ended abruptly, because he was not willing to support the racist politics – but also because he and his wife had the “wrong ancestors”.

One did not have to be Jewish to lose one’s standing under National Socialism. The case of student Kurt Lingens shows that even a rich, middle-class German background could not protect a person from being banned from studies. Lingens was an active communist and was forced to leave the university.

In addition to these cases of ostracism, there were a great many people who were forced to work in Stuttgart – such as the Soviet citizen Pauline Papkowa. Over 290 cases of forced labor at the Technical University during World War II are known. Facilities like the Laboratories for Materials Science benefited from this form of slavery.

Paul Peter Ewald, born in 1888, enjoyed a successful career in research as a professor of theoretical physics. His theories on x-ray crystallography were recognized worldwide. In 1928, he came to Technical University of Stuttgart and built a center for theoretical physics. He became rector in 1932.

The accusations: Political opponent, non-Arian wife

His political orientation was liberal. He hoped to be able to view the success of the National Socialist party in the Reichstag election of January 1933 as a temporary phenomenon. Ewald was a Protestant, but also had Jewish ancestors and was thus considered a “Mischling zweiten Grades” (second degree half-breed). His wife was considered a Jew. As a political opponent and “non-Arian”, he would have lost his position right away after the beginning of Nazi rule, according to the “Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums” (Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service). A bizarre exception in the haphazard law allowed him to remain in office: Ewald had fought as a German soldier in World War I.

In April 1934, he attended a conference of university rectors and witnessed that rectors of other universities accepted the dismissal of Jewish and politically opposed professors without any resistance whatsoever. Because he was “not able to share the opinion of the national government regarding the race issue,” he resigned as rector.

Outrage over racism at universities

Until 1937, Ewald witnessed increasingly racist attitudes at the university. In 1936, he had left a mandatory assembly of lecturers out of outrage over a communication by the Reichsminister for Science, Family, and Public Education. Dozentenführer (chief lecturer) Reinhold Bauder had read the memorandum about “the so-called ‘objectivity of science’”, which was said to be based on national sentiment. As a result, national socialist rector Wilhelm Stortz urged him to submit his request for dismissal from his position of professor. The “simplification of administration” introduced by the Nazis made it possible to shroud forced retirement for racist or political reasons in a cloak of legality.

Emigration to England

Thanks to good contacts, Ewald was able to emigrate to England in 1937. Colleagues had wanted to bring him abroad as early as 1933 – but he did not want to leave his position. Until 1940 he drew a paltry pension. He was, however, able to continue his career in the USA – a rare exception. His contact with the Technical University and later the University of Stuttgart, where two of his students had become professors, was revived during the 1950s. He passed away in the USA in 1985 at the age of 97.

The Soviet citizen Pauline Papkowa, born in 1916, is one of the 292 identified forced laborers who had to work at the Technical University of Stuttgart during World War II under inhumane conditions. Forced laborers were brought in from the regions occupied by the Wehrmacht: Poland, the USSR, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Yugoslavia, and Italy. The “Ostarbeiter” (eastern workers) from the Soviet Union were treated particularly badly. They were given very little food and subjected to physical violence. Many had been abducted; some were kidnapped right off the street. The treatment of “western” workers was only slightly better. Some had volunteered; however, this did not change the circumstances of their forced labor.

Abducted for clearing rubble

In 1941, German soldiers had forcibly pressed Pauline Papkowa into their service at her home near Leningrad. She had to clean, mend clothing, and do other household chores for the Wehrmacht. It is presumed that she was recaptured and taken to Germany after a failed attempt at flight. In 1944 she came to Stuttgart as an “Ostarbeiterin”, and initially was forced to help clear rubble. From late March 1944, she worked as a janitor at the Institute for Materials Science or Materialprüfungsanstalt (MPA). Her duties included sweeping the machine halls and courtyard on Friday and Saturday mornings. After August 1944, clearing rubble in Stuttgart took precedence, so that the MPA could no longer use Papkowa, although the institute tried to keep “its” cleaning women.

Ostracized even after the war

For many Soviet forced laborers, life continued to be disastrous even after returning to their homeland. Because they had served the enemy in Germany, the workers came under general suspicion. Often they lived for years on the margins of society in the furthest reaches of Siberia. Their rehabilitation was not completed until the 1970s.

Kurt Lingens, born in 1912, was a student from a rich, well-established family. At his parents’ urging, he began studying architecture at the Technical University of Stuttgart in the winter semester of 1931/32. He had turned to communism early in life, and became “1. Vorsitzender des Roten Studentenbundes” (1st Chairman of the Red Student Association) during his very first semester – according to records of the political police.

Banned from studies for political reasons

He was forced to abandon his studies as early as July of 1933 and banned from continuing his education at other German universities. Thanks to his ample financial resources, he was admitted to university in Vienna. When he met his wife Ella, and Austrian citizen, he soon turned to the more moderate political orientation of social democracy, which Ella shared. Both decided to study medicine and soon continued their education in Munich and Marburg. Lingens was able to circumvent the study ban.

Narrow escape from death

Although their son was born in 1939, Ella and Kurt Lingens started hiding Jews who were threatened with deportation to concentration camps in their apartments in 1940. In 1942, an informant of the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) implicated the couple. Ella Lingens, being a doctor, narrowly survived the extermination camp at Auschwitz; Kurt Lingens escaped with his life due to his deployment to a prison battalion in Russia.

After the war, the marriage faltered. Kurt Lingens emigrated to the USA in 1948. His medical training was not recognized until the mid-1960s. He died of an aneurism shortly after opening his practice.

Righteous among the Nations

In 1980, Ella and Kurt Lingens and their helper Baron Karl von Motesiczky, who had been murdered in Auschwitz, were honored as “Righteous among the Nations” by the memorial site Yad Vashem.

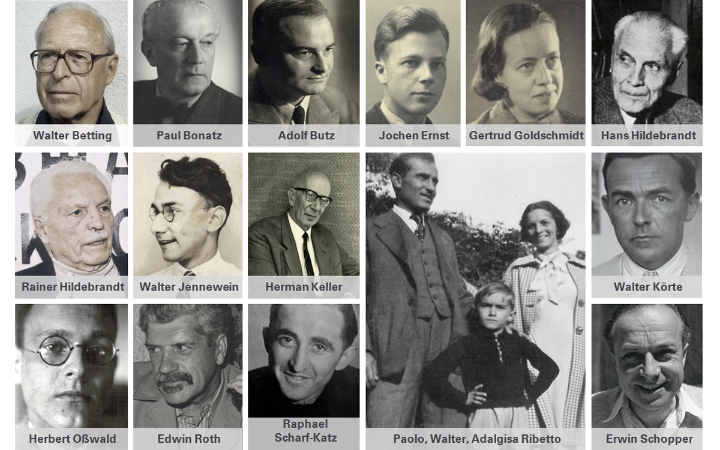

These personal histories are only three examples of the more than 440 people who experienced injustice at the hands of their colleagues, superiors, and the university during the National Socialist era until 1945. Any information still available today about the persecution and disenfranchisement of individuals was collected in the documentary by Norbert Becker and Katja Nagel.

The Question of Guilt

These cases move us because the environment in which they appeared is similar today. Stuttgart is still here, the Technical University is now the University of Stuttgart. There are people working as professors, students pursuing their educations in the sciences, other employees are organizing the administration and non-scientific operations. Every one of them has individual attitudes about society, politics, justice, and morality.

The university, or its predecessor, has accepted blame because it did not represent pure teaching and science. It allowed itself to be misused by its members, for instance by granting stipends and fee reductions to students not according to their performance but according to their party affiliations and commitment to NS organizations. Because dismissals from studies were not imposed by individuals but in the name of the university, the university must share the burden of guilt.

There is no such thing as unpolitical science.

“The University of Stuttgart wants to provide all students with an education that is not pure or neutral science. The concept of unpolitical science, as was the ideal after the war, does not exist. Science always shares in the responsibility for society. Especially in our time of globalization, it demands an atmosphere of tolerance and humanity. The constitutional state and freedom of science are inextricably linked.” Prof. Wolfram Ressel

Documentary and memory

- The goal

-

of the documentary was to identify by name all of the members of the Technical University or its successor, the University of Stuttgart, who were persecuted and deprived of their rights by the university or its agents during the years of National Socialist rule. In addition, the stories behind the injustices, the perpetrators, and their motives were told.

- The impulse

-

for the research and documentary was a request submitted to Rector Wolfram Ressel in 2013. He was asked to rehabilitate two students who had been forced to leave the university during the NS regime because of their homosexual orientation. The rector subsequently commissioned an investigation to find out how many such acts of injustice were committed.

- The availability of source material

-

has improved considerably compared to similar, older investigations at other universities, even though the university’s own archive was almost entirely lost to a fire in 1944. The files of the denazification trials (Tribunal files) and the reparation proceedings that arose after the end of World War II can be used now that data protection periods have expired.

Another available source of information is internet research, which helped to find more documents and families of victims. In addition, Norbert Becker was able to conduct several interviews with victims, but also with two NS student leaders, between 1997 and 2003.

- The book

-

has been available since 2017. It is also available as an e-book [de]. A small edition of 50 advance copies was distributed to the families of victims and to the media during the memorial event.

- Completeness

-

is not possible: The poor availability of information and the fact that many acts of persecution occurred without legal basis and written documentation make it likely that many cases will remain undiscovered.

- The term persecution

-

describes all measures that caused students to be banned from the university for racist or ideological reasons, and led scientists to be dismissed for the same reasons or end their university careers on their own initiative. The withdrawal of diplomas and doctorates and appointments to honorary citizen or honorary senator for racist or political reasons must also be taken into account.

- Countless forced laborers

-

were among the persecuted. They had to work at the Technical University involuntarily during World War II, or they were initially recruited as foreign laborers before being pressed into forced labor.

- A memorial book

-

is what the documentary represents for the Jewish members of the Technical University of Stuttgart who attended university during the NS regime. The authors included all Jewish students or those considered Jewish or “non-Arian” by the NS government – even those who were able to complete their studies at Technical University of Stuttgart (seemingly) without incident.

- The perpetrators

-

were deliberately researched individually and named in the documentary, provided the research yielded certainty about their identities. The impulse for this was the request from the family of a persecuted female student to also name the perpetrators.

This illustrates the events not as anonymous incidents, but as injustice deliberately inflicted by one person on another.

What the media reported

- Uni entschuldigt sich bei Angehörigen (University apologizes to families)

Videos and report, SWR Aktuell Baden-Württemberg, 6.2.2017, 18:00 Uhr - 440 Opfer von Unrecht und Verfolgung ermittelt (440 victims of injustice and persecution identified)

Report, Stuttgarter Zeitung, Heidemarie A. Hechtel, 7.2.2017 - Ungeist am Ort des Geistes (Demon in a place of the mind)

Commentary, Stuttgarter Zeitung, Jan Sellner, 7.2.2017 - Ein dunkles Kapitel dokumentiert (A dark chapter documented)

Report, Südwest Presse, Raimund Weible,7.2.2017 - Universität arbeitet eigene NS-Geschichte auf (University works through own NS history)

Report, Eßlinger Zeitung, Tim Seitter, 7.2.2017 - Gedenkveranstaltung an Universität Stuttgart (Memorial event at University of Stuttgart)

Video, Regio TV Stuttgart, 7.2.2017

Contact

Helen Wiedmaier

Dr.University Archives (Head)